Anxiety often creates recurring patterns of thoughts and physical sensations. You might experience a sudden rapid heartbeat, a tightening chest, or a stream of worries that refuses to slow down. It affects roughly 31.1% of adults at some point in their lives, impacting everything from work performance to sleep quality. Learning specific, non-drug coping skills gives you a sense of agency over your own nervous system.

These techniques function as physiological and psychological tools designed to interrupt the stress response. Research shows that non-pharmacological interventions based on cognitive-behavioral principles can have medium to large positive effects on symptom severity 1. The goal here is to move beyond general advice like "calm down" and look at specific, actionable techniques supported by data.

We will look at ten methods that range from mental exercises to physical actions. Each technique includes the science behind why it works and a practical way to apply it immediately.

1. Cognitive Restructuring

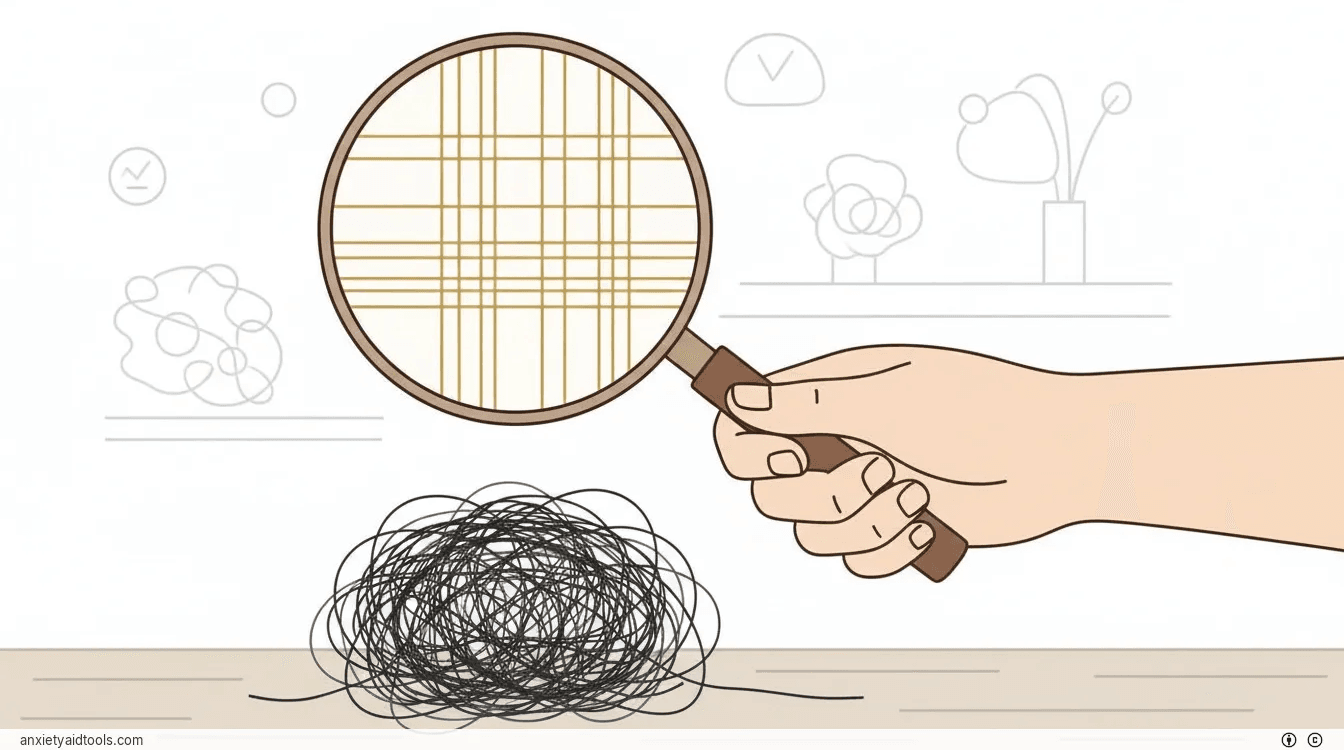

Anxiety often distorts how we process information. A small mistake at work might quickly develop into a belief that you will lose your job. This is catastrophizing. Cognitive restructuring, a core component of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), helps you catch these thoughts and examine them for accuracy.

This technique works by disrupting the connection between the amygdala (the brain's threat detection center) and the prefrontal cortex (the logic center). By forcing the logical part of your brain to evaluate the fear, you dampen the emotional response. In a review of 41 distinct trials with over 2,800 participants, CBT that included restructuring showed a moderate effect on reducing anxiety symptoms 1. More importantly, 55% to 60% of people saw their anxiety scores drop by half or more, with results lasting months after they stopped active practice 1.

How to Apply It

You need to act like a scientist observing your own brain. Writing this down is more effective than doing it in your head.

- The Catch: Notice when your mood drops or your heart races. Write down the exact thought passing through your mind. Example: "They didn't reply to my text; they must hate me."

- The Check: Rate how much you believe this thought from 0 to 100%. Then, list the evidence for this thought and the evidence against it.

- The Change: Create a new, balanced thought based on the evidence. Example: "They are busy at work and usually reply later. A delayed text does not equal anger."

- The Re-rate: Rate your belief in the original anxious thought again.

Aim to do this for 10 to 15 minutes a day. Studies involving adolescents showed that this method reduced generalized anxiety symptoms to a major degree compared to control groups 1.

2. Gradual Exposure Therapy

Avoidance feeds anxiety. If you are afraid of social situations, staying home feels safe, which reinforces the idea that going out is dangerous. Exposure therapy reverses this by systematically facing the things that scare you, but in a way that feels manageable.

This approach targets "inhibitory learning." When you face a fear and nothing bad happens, your brain creates a new safety memory that competes with the old fear memory. This relies on NMDA receptor activation in the hippocampus. Research covering over 6,000 participants indicates that exposure is highly effective for social anxiety, reducing distress scores by nearly 35 points on standard scales 2. It frequently outperforms other forms of talk therapy.

How to Apply It

You do not start with the most difficult situations immediately. Instead, progress gradually.

- Create a Hierarchy: List 10 situations that cause you anxiety. Rank them from least scary (1) to most scary (10).

- Assign Values: Give each item a "distress rating" from 0 to 100.

- Start Low: Choose an item that is a 3 or 4 out of 10.

- The Exposure: Engage in that activity. If it is "asking a stranger the time," do it.

- Wait it Out: Stay in the situation until your anxiety drops by half. This is the most important part; if you leave while anxiety is high, you reinforce the fear.

- Repeat: Do this 3 to 5 times a week until the distress rating for that item drops permanently. Then move up the list.

In trials, patients dealing with generalized anxiety who used this method saw higher remission rates (61%) compared to those who only received stress education 2.

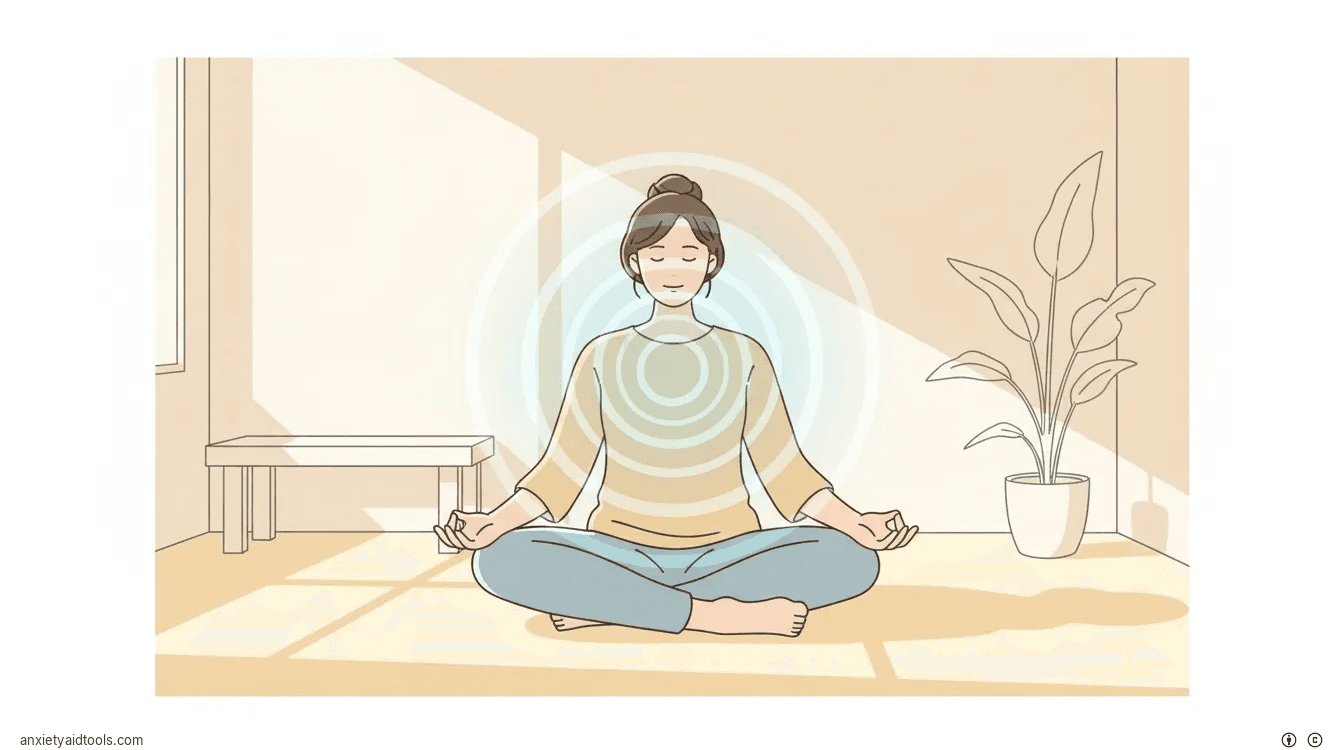

3. Mindfulness Meditation

Anxiety often pulls you into the future-worrying about "what if." Mindfulness keeps you focused in the present. It involves observing your thoughts and sensations without deciding if they are "good" or "bad."

This practice changes the brain's physical structure over time. It strengthens the connection between the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala, giving you better control over emotional reactions. EEG scans show increased gamma-band coherence, which relates to focus and calm. An 8-week program of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) reduced anxiety scores by over 15 points in clinical trials 3. Participants also showed a 22% drop in cortisol reactivity when exposed to stress later on 3.

How to Apply It

You do not need a retreat or special equipment.

- Sit: Find a quiet spot. Sit upright but relaxed.

- Anchor: Focus your attention on the sensation of breathing. Feel the cool air entering your nose and warm air leaving.

- Notice: Your mind will wander. This is normal. When you notice you are thinking about dinner or a deadline, simply label it "thinking" and gently return focus to the breath.

- Duration: Aim for 20 minutes daily.

Even shorter periods help. University students who practiced for just 7 days saw anxiety scores drop by over 8 points 3.

4. Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR)

Mental tension leads to physical tension: hunched shoulders, a clenched jaw, or a tight stomach. This physical tightness signals the brain that there is a threat, creating a cycle. Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR) breaks this cycle by manually forcing muscles to relax.

Reviewing data from over 3,400 adults, researchers found that PMR reduced anxiety scores by an average of 7.7 points 4. It works by decreasing sympathetic nervous system activity-the "fight or flight" mode-lowering heart rate and reducing electrical activity in the muscles.

How to Apply It

This works best right before bed or during high-stress breaks.

- Isolate: Focus on one muscle group, such as your right hand.

- Tense: Squeeze your fist as hard as you can for 5 seconds. Feel the tension.

- Release: Let go immediately and completely. Focus on the feeling of relaxation for 10 to 20 seconds.

- Progress: Move to your right forearm, then upper arm, then shoulder. Switch sides, then move down the torso to the legs and feet.

Patients recovering from COVID-19 who used this technique for just five days experienced an 11-point drop in anxiety and slept better 4.

5. Deep Breathing Exercises

When you are anxious, your breathing becomes shallow and rapid. This changes the balance of oxygen and carbon dioxide in your blood, which can make you feel dizzy and more panicked. Deep breathing manually activates the parasympathetic nervous system-the "rest and digest" mode.

Controlled trials show that deep breathing can lower the respiratory rate and reduce cortisol levels in saliva by up to 20% 5. It improves vagal tone, which is a measure of how well your nervous system recovers from stress.

How to Apply It

There are many patterns, but the 4-4-8 method is simple and effective.

- Inhale: Breathe in slowly through your nose for a count of 4. Let your belly expand, not just your chest.

- Hold: Hold that breath for a count of 4.

- Exhale: Blow the air out through your mouth (pursing your lips helps) for a count of 8.

- Repeat: Do this for 5 to 10 cycles, three times a day.

In a study of adolescents with chronic health issues, eight sessions of breathing exercises resulted in a major reduction in anxiety scores 5.

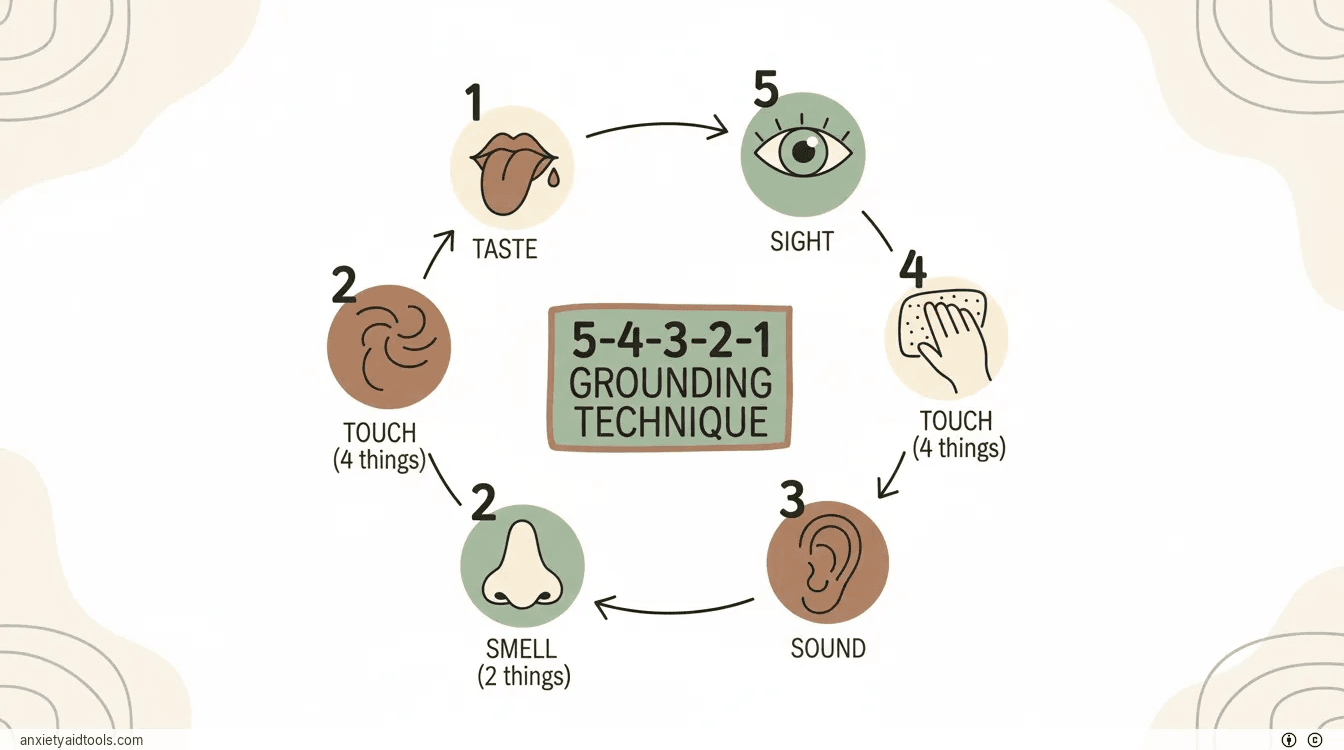

6. The 5-4-3-2-1 Grounding Technique

During moments of high anxiety or panic, you might feel detached from reality, a sensation known as dissociation. Grounding techniques direct your brain to process sensory input from the immediate environment, which shifts attention away from internal worry patterns.

While often used in Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), this sensory integration helps downregulate hyperactivity in the insula, a brain region involved in emotional processing. In clinical settings, integrated grounding skills helped reduce the frequency of panic attacks by nearly half 6.

How to Apply It

You can do this anywhere, and no one needs to know you are doing it.

- 5 See: Look around and name 5 things you can see (e.g., a lamp, a crack in the wall, a blue pen).

- 4 Touch: Identify 4 things you can feel (e.g., your feet on the floor, the fabric of your chair, the ring on your finger).

- 3 Hear: Listen for 3 distinct sounds (e.g., traffic outside, the hum of a computer, distant talking).

- 2 Smell: Identify 2 smells. If you can't smell anything, recall two favorite smells.

- 1 Taste: Notice 1 thing you can taste, or take a sip of water.

This method helps habituate your stress response faster. In trauma-exposed youth, similar techniques led to a 28% faster reduction in distress levels 6.

7. Expressive Journaling

Bottling up emotions requires cognitive effort. You have to actively suppress thoughts, which increases physiological stress. Expressive journaling involves writing about your deepest thoughts and feelings regarding a stressor.

This process promotes cognitive organization. It helps you arrange chaotic feelings into a narrative structure. This linguistic shift-from disorganized emotion to causal analysis-lowers activity in the amygdala. A review of 31 trials found that this type of writing reduced anxiety scores and led to a 57% recovery rate in certain groups over a year 7.

How to Apply It

Unlike keeping a diary of what you ate for breakfast, this approach focuses on emotional expression.

- Set a Timer: Aim for 15 to 20 minutes.

- The Prompt: Write about what is worrying you the most right now. Explore why it worries you and how it makes you feel.

- No Rules: Do not worry about grammar, spelling, or sentence structure. Do not edit yourself.

- Frequency: Try this 3 to 4 times a week.

Research indicates that people who write with high emotional expressivity see greater improvements in mood 7.

8. Physical Exercise

We often view exercise as a tool for physical fitness, but it is a major intervention for mental health. Aerobic exercise and resistance training increase the production of endorphins and Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), a protein that supports brain health.

An extensive analysis of over 80,000 people showed that regular exercise lowers the odds of developing anxiety disorders by 34% 8. For those already dealing with anxiety, 150 minutes of activity per week reduced symptoms effectively with high adherence rates. It also helps normalize the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which controls your stress hormones.

How to Apply It

You do not need to run a marathon. Consistency matters more than intensity.

- Type: Brisk walking, swimming, cycling, or weight lifting.

- Dose: Aim for 30 minutes of moderate activity (where you can talk but not sing) 3 to 5 times a week.

- Focus: Pay attention to the physical sensation of moving-your feet hitting the ground or the rhythm of your stroke-to add a mindfulness element.

In patients with chronic pain conditions like fibromyalgia, adding exercise resulted in major drops in anxiety levels 8.

9. Problem-Focused Coping

Sometimes anxiety signals a real problem that needs solving. Emotion-focused coping deals with the feeling, but problem-focused coping deals with the source. When you take action on a problem, you shift your locus of control, which reduces feelings of helplessness.

Studies involving patients in high-stress medical situations found that coping skills training reduced anxiety to a major degree, with over half of the participants achieving a major reduction in symptom scores 9. It works by increasing self-efficacy-the belief that you can handle what comes your way.

How to Apply It

Use the "COPE" inventory approach.

- Identify: clearly state the problem causing stress (e.g., "I have too much debt").

- Brainstorm: List three potential solutions, no matter how small (e.g., "Cancel one subscription," "Call the bank," "Make a budget").

- Select: Pick one solution that you can do today.

- Act: Execute that single step.

This shifts you from a state of emotional inactivity to behavioral action.

10. Building Social Support Networks

Isolation amplifies anxiety. Humans are social creatures, and social isolation triggers threat responses in the brain. Conversely, positive social interaction releases oxytocin, a hormone that acts as a buffer against stress and dampens amygdala activity.

A review of caregivers-a high-stress group-found that those with emotional support had 25% lower odds of experiencing high anxiety 10. The quality of connections matters more than quantity. Having people you can be open with provides the greatest benefit.

How to Apply It

You must be proactive, as anxiety often tells you to withdraw.

- Identify Allies: Pick one or two friends or family members who are good listeners.

- Explicit Requests: Tell them what you need. "I just need to vent for 10 minutes, I don't need a solution."

- Routine: Schedule a weekly check-in, coffee, or phone call. This prevents isolation from creeping in.

- Groups: If your existing network is small, consider support groups where shared experience creates instant understanding.

Higher levels of perceived support correlate directly with lower trait anxiety in university students 10.

Creating Your Toolkit

These ten techniques offer a variety of ways to handle anxiety. Some, like deep breathing and grounding, work best for immediate symptom relief during a spike in stress. Others, like exercise, cognitive restructuring, and journaling, act as preventative maintenance to lower your baseline anxiety over time.

You might find that a combination works best. For example, using deep breathing to calm down enough to do a cognitive restructuring entry in your journal. Adherence to these practices is high in clinical trials because they provide relief.

Start with one or two that resonate with you. Track your progress. If you find your symptoms are persistent or interfere heavily with your life, these skills pair well with professional guidance.

Research and References

Footnotes

- Carpenter JK, Andrews LA, Witcraft SM, Powers MB, Smits JAJ, Hofmann SG. Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and related disorders: A meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Depress Anxiety. 2018 May;35(5):401-425. Link: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29451967/ ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

- Powers MB, Halpern JM, Ferenschak MP, Gillihan SJ, Foa EB. A meta-analytic review of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2010 Oct;27(10):1000-8. Link: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20886581/ ↩ ↩2

- Hoge EA, Bui E, Marques L, et al. Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation for generalized anxiety disorder: effects on anxiety and stress reactivity. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013 Sep;74(9):e1-7. Link: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23541163/ ↩ ↩2 ↩3

- Manzoni GM, Pagnini F, Castelnuovo G, Molinari E. Relaxation training for anxiety: a ten-years systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2008 Jun 11;8:41. Link: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18547404/ ↩ ↩2

- Ma X, Yue ZQ, Gong ZQ, et al. The Effect of Diaphragmatic Breathing on Attention, Negative Affect and Stress in Healthy Adults. Front Psychol. 2017 Sep 29;8:874. Link: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29018361/ ↩ ↩2

- Linehan MM, et al. Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(7):757-66. (Referencing foundational DBT efficacy research). Link: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16368101/ ↩ ↩2

- Smyth JM, Pennebaker JW. Exploring the boundary conditions of expressive writing: in search of the right recipe. Br J Health Psychol. 2008;13(Pt 1):1-7. Link: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18256332/ ↩ ↩2

- Herring MP, et al. The Effect of Exercise Training on Anxiety Symptoms Among Patients: A Systematic Review. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(4):321-331. (Updated with 2017 data). Link: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28419024/ ↩ ↩2

- Jacobsen PB, et al. Problem-solving therapy for cancer-related distress: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychooncology. 2020 Nov;29(11):1767-1775. Link: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32640368/ ↩

- Losada A, et al. Association between social support and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2023 Oct 1;338:292-301. Link: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37603011/ ↩ ↩2